LLM-based Agents

Towards Agentic AI

Introduction

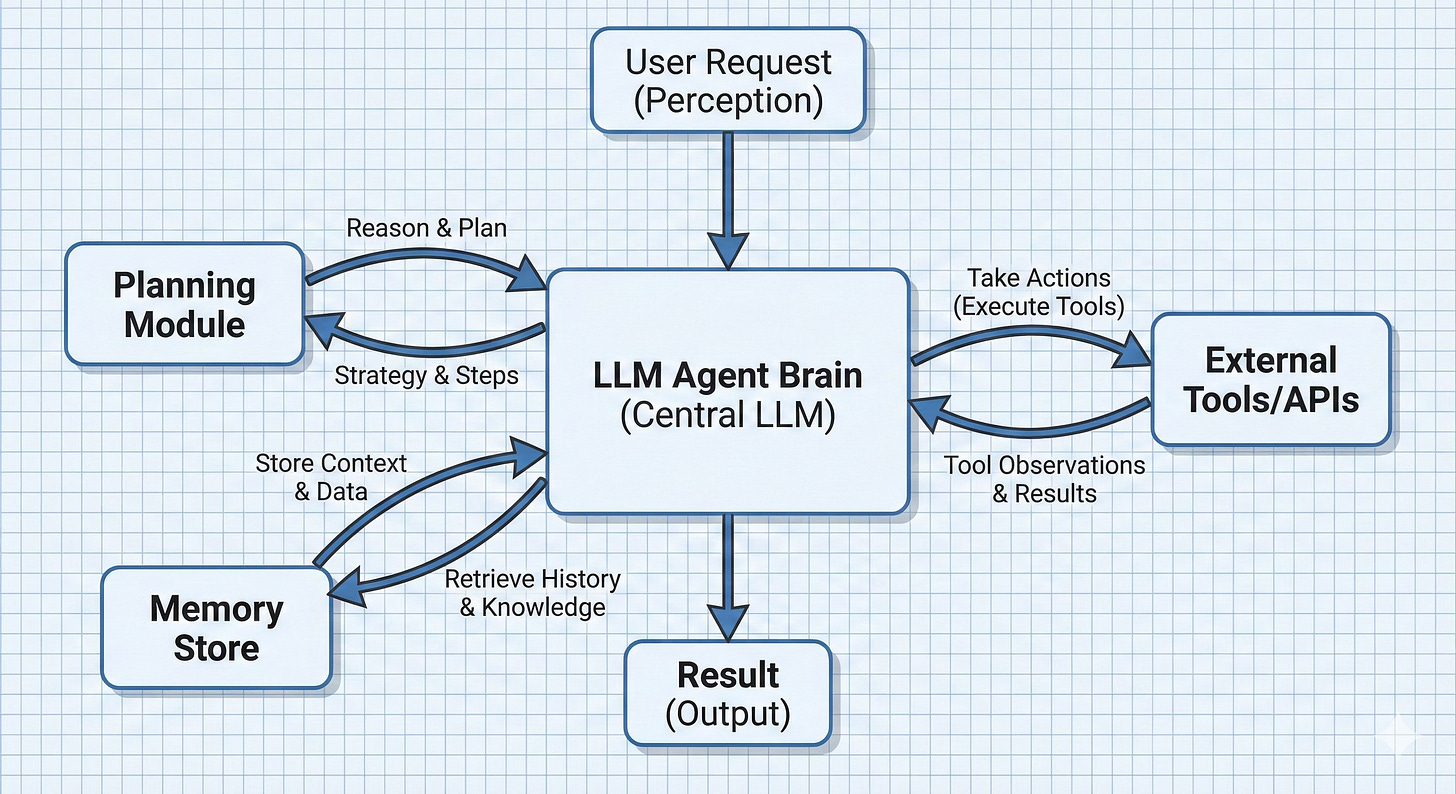

Large Language Model-based agents represent a fundamental paradigm shift from static text generation to autonomous, goal-directed systems capable of environmental interaction and multi-step reasoning. An LLM by itself is essentially a textual oracle: it takes a prompt and generates a completion. It cannot perform real actions in the world or fetch new information once trained – its world begins and ends with the text in its prompt context. An LLM-based agent wraps an LLM inside an execution loop: observe → decide → act → observe. The LLM proposes the next action (often a tool call), the system executes it in an environment (web, Python REPL, IDE, enterprise APIs), and the resulting observation is fed back into the LLM. Over multiple steps, the agent can gather information, run computations, recover from errors, and converge on a final outcome rather than betting everything on a single response.

For example if a user asks for an analysis of health trends over the last decade, including a chart of obesity rates. A standalone LLM might lack up-to-date data or charting capabilities, but an agent could search for recent health reports, fetch data, run code to generate a chart, and then compose an answer with the chart included.

At a high level:

Agent ≈ LLM (policy) + Tools + Orchestrator/Loop + Memory

The core logic is a loop that feeds the LLM observations and context, lets it decide an action, executes the action (tool call), and then feeds the results back in . This loop continues until the task is complete or a stopping condition is reached . The magic of agents is not just in the LLM itself, but in this surrounding architecture that allows the LLM to interact with the world. A standard chatbot might be an expert consultant locked in a room with no internet; an LLM agent is that consultant given a computer, internet access, and the ability to run programs – it can actively do things, not just talk about them.

Two popular agentic applications are:

Data Analysis Assistant: An agent that answers complex analytical questions (like the health trends query) by searching for information and using tools (e.g. a code interpreter) to analyze data and produce results.

Software Coding Agent: An agent that assists in software development, capable of writing code, running it in a sandbox, debugging errors, and iterating until a task (like generating a correct function or app) is completed.

In the sections that follow, we delve into LLM-based agents, the core components of their architecture, common design patterns, training and optimization approaches, key challenges, and the areas where they are most impactful. We will sketch a minimal agent workflow using (pseudo) code.

Minimal Agent

In this section, we will define a minimal agent loop. This will act as our sketchpad. First, the agent can call tools and we need to parse the response to extract the name and arguments for the tool e.g. tool=weather and location=Seattle that we can send to the tool (API).

@dataclass

class AgentAction:

kind: str # “tool”, or “final”

tool_name: Optional[str] = None

tool_args: Optional[Dict[str, Any]] = None

answer: Optional[str] = None

def parse_agent_output(raw: str) -> AgentAction:

“”“

Parse model output into:

- a tool call, or

- a final answer.

“”“

# Pseudocode: parse json to extract tool or final response

...With this action space, an agent can be sketched as follows. To keep the loop robust, we’ll assume the model outputs one of two JSON objects only - a tool invocation or a final answer. This avoids brittle string parsing and mirrors how most production systems structure tool calls.

class Agent:

def __init__(self, llm: PolicyLLM, tools: ToolRegistry):

self.llm = llm

self.tools = tools

def run(self, user_request: str, max_steps: int = 16) -> str:

“”“

Run a single agent episode: from user_request to final answer.

“”“

state: List[str] = [] #list of log lines: thoughts, actions, observations

for step in range(max_steps):

prompt = build_agent_prompt(user_request, state, self.tools.spec())

raw_output = self.llm.generate(prompt)

action = parse_agent_output(raw_output)

if action.kind == “final”:

return action.answer or “”

elif action.kind == “tool”:

obs = self.tools.call(action.tool_name, action.tool_args or {})

# Append to short-term memory

state.append(f”Action[{step}]: {action.tool_name}({action.tool_args})”)

state.append(f”Observation[{step}]: {obs}”)

else:

raise ValueError(f”Unknown action kind: {action.kind}”)

# Fallback if no final answer within max_steps

return “I couldn’t complete this task in the allotted steps.”Basically, the agent is a loop of actions until the final response is reached.

The interesting pieces are:

build_agent_prompt(...): how you pack user request, history, and tool specs into a prompt.parse_agent_output(...): how you interpret the model’s output as a tool call vs final answer.

We will fill-in these and other details as we progress in this discussion. The reminder of this post is about making this loop executable, smarter, safer, and trainable.

Architecture of an LLM Agent

LLM agents are modular systems. At a high level, we can think of an LLM-based agent as having several core components working in unison.

Policy LLM

At the heart of the agent is a LLM which is the policy model that decides what to do next given the current state. The LLM is prompted with the current context (which may include the user query, conversation history, retrieved knowledge, tool results, etc.) and asked to generate the next action or output. We call it a policy because it maps states to actions, akin to a policy in reinforcement learning.

class PolicyLLM:

def __init__(self, model):

self.model = model

def generate(self, prompt: str) -> str:

# Wrap the inference call here

return self.model(prompt)Tooling Interface

One of the most distinctive aspects of LLM agents is their ability to use external tools. A tool can be an API, a database, a code execution sandbox, a web browser, a calculator, or even another ML model. The tooling layer provides a bridge between the LLM’s text-based world and these external functionalities.

To enable an LLM to use tools, the agent framework defines an interface or schema for each available tool which describes how to invoke it. In practice, this often means describing the tool’s name, its function signature (inputs/outputs), and giving examples. For example, an enterprise agent might register a tool for HR data:

getEmployeeRecord(name: String) -> EmployeeRecord.

Modern agent implementations use structured schemas like JSON or function-call specifications to make tool use reliable. This registration (often done in a system prompt or via an API specification file) tells the LLM that such a function exists and how to call it . When the LLM decides that it needs that data, it can output a structured function call which the agent executor will parse and run.

A common pattern is to provide a JSON Schema per tool (many APIs and frameworks support variants of this).

{

“type”: “function”,

“function”: {

“name”: “search_database”,

“description”: “Query the knowledge base for relevant documents”,

“parameters”: {

“type”: “object”,

“properties”: {

“query”: {”type”: “string”, “description”: “Search query”},

“max_results”: {”type”: “integer”, “default”: 5}

},

“required”: [”query”],

“additionalProperties”: false

},

“strict”: true

}

}With this schema, let’s define a registry for tools:

from dataclasses import dataclass

from typing import Any, Dict, List, Callable, Optional

@dataclass

class Tool:

name: str

description: str

fn: Callable[[Dict[str, Any]], Any]

parameters: Dict[str, Any] # JSON Schema for the arguments

class ToolRegistry:

def __init__(self, tools: List[Tool]):

self._tools = {t.name: t for t in tools}

def call(self, name: str, args: Dict[str, Any]) -> Any:

if name not in self._tools:

raise ValueError(f”Unknown tool: {name}”)

return self._tools[name].fn(args)

def spec(self) -> List[Dict[str, Any]]:

“”“

Return tool specs in the JSON-schema / function-calling style,

“”“

return [

{

“type”: “function”,

“function”: {

“name”: t.name,

“description”: t.description,

“parameters”: t.parameters,

“strict”: True,

},

}

for t in self._tools.values()

]Common tools that are used in current LLM agents are:

Web and Knowledge Bases: Agents can connect to the internet or internal knowledge bases to fetch up-to-date information. This is usually done via search APIs, database queries, or custom knowledge retrieval tools. For example, a research assistant agent might have a Wikipedia or academic paper search interface. The observation coming back might be a chunk of text that the LLM then parses to extract facts.

Code Interpreters and REPLs: Many agents use code execution as a powerful tool. This effectively lets the agent do math, data processing, or any computable operation beyond its direct trained knowledge. The agent generates a code block, which the tool runs and output or error are returned as text or files, which the agent then reads.

Operating System and Files: Advanced agents might interface with the OS – reading/writing files, controlling applications, or managing processes. An example is OS-Copilot, which aims to let an agent interact with elements of a user’s OS (web browser, terminals, files, etc.) in an integrated way . Such an interface is obviously sensitive, so it’s often heavily sandboxed or permissioned. Nonetheless, this enables use cases like an agent that can open your calendar app to schedule meetings, or read a file from your filesystem.

Embodied or Robotic Interfaces: In some cases, the environment is a physical or simulated world. For instance, consider an agent controlling a robot or a game character. The tool interface might be a simulator’s API (e.g., an agent gets observations like camera input or game state and can take actions like moving or pressing buttons). A concrete example is Voyager, an agent that uses GPT-4 to play Minecraft by reading the game state and writing code to act within the game . Here the tool is essentially the game’s command interface.

When the agent uses these interfaces effectively, it achieves a kind of extensibility i.e. it’s not limited to its training data or built-in functions, it can leverage external systems on the fly to solve tasks.

Tool-using LLM

Crucially, the LLM in an agent is not just generating final answers, but also tool calls and intermediate reasoning. For this, we need to instruct the LLM in the right way, it needs to be aware of the tools and how to invoke them.

In the system prompt we:

Define the agent’s role (“You are a data analysis agent…”).

Describe available tools and their calling convention.

Specify the protocol (e.g., Thought → Action → Observation).

Set guardrails (“Never run code that accesses the network.”).

A typical system prompt would look like:

SYSTEM_PROMPT = “”“

You are a capable agent.

You have access to the following tools:

{tool_descriptions}

When you need to use a tool, you MUST respond with a JSON object ONLY, no extra text, of the form:

{{”type”: “tool”,

“name”: “<tool_name>”,

“args”: {{ ... JSON arguments ... }}

}}

When you want to return the final answer to the user, respond with:

{{”type”: “final”,

“answer”: “<natural language answer for the user>”}}

....

“”“which this system prompt, we can now build the agent prompt (build_agent_prompt discussed above):

def format_tool_descriptions(tools_spec: List[Dict[str, Any]]) -> str:

“”“

tools_spec is a list of {

“type”: “function”,

“function”: {

“name”: ...,

“description”: ...,

“parameters”: {...},

“strict”: true

}

}

“”“

return “\n”.join(

f”- {t[’function’][’name’]}: {t[’function’][’description’]}”

for t in tools_spec

)def build_agent_prompt(

user_request: str,

state: List[str],

tools_spec: List[Dict[str, Any]],

) -> str:

tool_desc = format_tool_descriptions(tools_spec)

history = “\n”.join(state)

return f”“”{SYSTEM_PROMPT.format(tool_descriptions=tool_desc)}

User request:

{user_request}

Interaction so far:

{history}

Now respond with either a tool invocation JSON or a final answer JSON.

“”“The LLM’s output thus can be either a thought, an action, or a final answer. If the agent generates a tool call, we need to extract the arguments (e.g. tool=search_web and query=”quantum mechanics”) from it that can be passed to the tool interface (search_api) to run it a produce output (HTML contents).

import json

def parse_agent_output(raw: str) -> AgentAction:

obj = json.loads(raw)

if obj[”type”] == “tool”:

return AgentAction(

kind=”tool”,

tool_name=obj[”name”],

tool_args=obj.get(”args”, {}),

)

elif obj[”type”] == “final”:

return AgentAction(

kind=”final”,

answer=obj[”answer”],

)

else:

raise ValueError(f”Unexpected agent output type: {obj[’type’]}”)This LLM often runs in a loop (thinking and acting repeatedly) rather than a single shot.

Environment Interfaces

The environment interface refers to how the agent perceives and affects the outside world beyond the LLM’s internal reasoning. This is closely tied to the tools discussed earlier, each tool is a channel through which the agent can observe or manipulate some part of the world.

Once we’ve given an agent tools, we still need to decide where those tools operate. That “where” is the environment: the playground the agent lives in while it’s working on a task. We can think of the environment as the world the agent is embedded in during an episode. The agent doesn’t directly see or modify everything in that world; it interacts with it through tools. Each time a tool runs, the environment changes (or not) and sends something back an observation which might be:

a value (e.g. a DataFrame summary),

a document or page,

a test log,

an error message or exception.

Those observations are exactly what we feed back into the LLM on the next step. Below are a few common environments you see in LLM-based agents.

Python / Data Science Sandbox

A very common environment is a sandboxed Python REPL:

The world contains: variables (e.g. df for a dataset), imported libraries (pandas, numpy, etc.), in-memory state that persists across code runs in the same session.

The agent acts by running code e.g. “load this CSV”, “group by region”, “plot a histogram”.

The environment returns: printed output, computed values, error traces if something fails, sometimes generated files (plots, reports).

A simplified (bare-bones) python sandbox executor can be defined as:

import io

import contextlib

import traceback

import re

class SimpleExecutor:

def __init__(self, global_vars: dict = None):

# Initialize with standard globals or custom ones (like datetime)

self.globals = global_vars if global_vars else {}

def execute(self, code: str):

# Basic safety check for input/os.system

if re.search(r”(\s|^)?(input|os\.system)\(”, code):

return “”, “RuntimeError: Forbidden command”

buffer = io.StringIO()

try:

# Capture stdout while executing

with contextlib.redirect_stdout(buffer):

exec(code, self.globals)

return buffer.getvalue().strip(), “Done”

except Exception:

# Return empty result and the error trace

return “”, traceback.format_exc().strip()

def batch_apply(self, code_list: list):

# Simple list comprehension instead of multiprocessing pool

return [self.execute(code) for code in code_list]This is not a secure sandbox; it’s a teaching example. Real systems use OS-level sandboxing (containers/VMs), syscall filters, and restricted interpreters.

Browser / Web Navigation

Another important environment is a browser or web navigation setup:

The world includes: the current URL and page content, the DOM structure, navigation history, cookies/session state (if you allow it).

The agent can: open URLs, click on elements, fill in forms, scroll or move between pages.

The environment sends back: HTML or extracted text, metadata (titles, links), HTTP errors or timeouts.

Here, a “step” in the episode could be “open this page and read the contents” or “click the first result and see what’s there”. The observations become context for the LLM to decide what to do next.

IDE / Project Directory

For coding agents, the environment is often an IDE plus a project directory:

The world consists of: a file tree (source files, configs, tests), the version control state (e.g. current branch, diff), available build/test commands.

The agent can: read and write files, run tests or a build, inspect diffs or logs.

Observations include: file contents, compiler errors, test results and stack traces, output from linters or formatters.

A repo debugging agent moves around in this environment: it inspects files, edits them, runs tests, and uses the resulting logs to steer its next edits.

Enterprise Systems and APIs

In many practical applications, the environment is a set of enterprise systems:

The world contains: CRM records, tickets, and cases, knowledge base articles, calendars, emails, internal dashboards, business metrics and logs.

The agent can: query or filter records, create or update tickets, send draft emails, log notes or outcomes.

Observations are: search results and record details, success/failure codes from APIs, status messages from workflow systems.

A support agent, for example, lives in this kind of environment: it pulls up user history, checks ticket status, updates fields, and drafts responses, all based on what these systems return.

Memory (Short-term and Long-term)

Memory is what allows an agent to remember what has happened so far and use it for future decisions. Traditional LLMs are constrained by their context window – they only “remember” the conversation up to a few thousand tokens. LLM-based agents augment this with explicit memory modules so they can handle extended interactions or even retain knowledge across sessions.

There are generally two types of memory in an LLM agent :

Short-Term Memory: This is the transient memory contained in the immediate context fed into the LLM. It includes the recent conversation or the current scratchpad of the agent (e.g. the chain-of-thought, recent actions and observations). In each cycle of the agent loop, the prompt given to the LLM includes a summary of what it has done so far (or possibly the full log if it fits) – this serves as short-term memory. For example, a coding agent keeps a running log of its steps: what functions it’s written, what error it saw when running tests, what it tried next. This log (or a compressed version) is in the prompt each time so the agent remembers the state of the coding task.

Long-Term Memory: Long-term memory allows the agent to retain information beyond the context window by storing it in an external database or vector store. This often takes the form of a knowledge base or vector memory. The agent can push important facts or observations into a store and later retrieve them when relevant . For instance, after the data analysis agent completes the obesity trend analysis, it might store the key data findings or the final report in a knowledge base for future reference. Weeks later, if asked a related question, the agent can look up those past results instead of starting from scratch. Long-term memory is typically implemented with embeddings, the agent represents textual information as vectors and uses similarity search to fetch relevant past items when needed . This allows scaling beyond the fixed limits of the LLM’s own memory.

Many agents employ hybrid memory structures that combine short-term and long-term memory . For example, an agent might have a rolling window of recent dialogue (short-term) plus the ability to query a vector store of all prior dialogues or documents (long-term) when the current query seems related to past contexts.

class AgentMemory:

def __init__(self):

self.short_term = [] # Recent messages in context

self.vector_db = VectorStore() # Long-term semantic storage

def retrieve(self, query: str, k: int = 5) -> List[Document]:

embeddings = embed(query)

return self.vector_db.similarity_search(embeddings, k=k)

def persist(self, content: str, metadata: dict = None):

“”“Store in long-term vector memory for future retrieval.”“”

self.vector_db.add(embed(content), content, metadata)

def add_to_context(self, query: str) -> None:

“”“Append to short-term (in-prompt) memory.”“”

self.short_term.append(query)

def build_context(self, query: str) -> dict:

return {

“short_term”: self.short_term[-10:],

“retrieved”: self.retrieve(query),

“current_query”: query

}One interesting implementation is the “Ghost in the Minecraft” (GITM) agent, which stored experiences in a key-value memory: the keys were natural language descriptions and the values were embedding vectors – effectively bridging symbolic and vector memory . This let the Minecraft agent recall specific experiences (like “I built a crafting table before”) when facing a similar situation again by semantic search.

Memory is essential for long-horizon tasks. Without memory, a coding agent wouldn’t recall what functions it already wrote or what the user’s requirements were after a few steps. The agent’s memory module often also handles state summarization – condensing the conversation or tool outputs when they get too large. Summarizing or selectively remembering relevant details is itself a skill the LLM can be tasked with (sometimes a dedicated summarizer model is used).

With memory, our agent becomes:

class Agent:

def __init__(self, llm: PolicyLLM, tools: ToolRegistry, memory: AgentMemory):

self.llm = llm

self.tools = tools

self.memory = memory

def run(self, user_request: str, max_steps: int = 16) -> str:

for step in range(max_steps):

prompt = build_agent_prompt(

user_request,

state=self.memory.short_term,

tools_spec=self.tools.spec(),

)

raw_output = self.llm.generate(prompt)

action = parse_agent_output(raw_output)

if action.kind == “final”:

return action.answer or “”

elif action.kind == “tool”:

obs = self.tools.call(action.tool_name, action.tool_args or {})

self.memory.append(

f”Action[{step}]: {action.tool_name}({action.tool_args})”

)

self.memory.short_term.append(

f”Observation[{step}]: {obs}”

)

return “I couldn’t complete this task in the allotted steps.”Common Architectural and Operational Patterns

LLM-based agents can be arranged and deployed in various patterns depending on the use case. Here we outline some common architectural and operational patterns that have emerged, from simple single-agent loops to orchestrated multi-agent systems and workflows.

Single-Agent with Tool Use (ReAct Loop Pattern)

The most basic pattern is an LLM agent operating alone with a set of tools, continuously reasoning and acting until it solves the task. The agent uses one LLM (potentially with internal chain-of-thought) and has access to one or more tools via the interface layer.

How it works: The agent starts with a user query or goal. It enters a loop:

Observe state: The agent considers the current state (initially the user query; later, the accumulating memory of what’s been done).

Decide action (thought → action): The LLM, given the state, produces either an action (tool invocation) or an answer. This decision is guided by the prompt which typically says something like “If you have not answered the question, think of what to do next. You can use these tools or give a final answer.”

Execute action: If the LLM chose a tool, the agent calls that tool and gets the result.

Record observation: The result of the tool is added to the agent’s context (often phrased like: Observation: [tool result]).

Loop or terminate: This new context is fed back into the LLM for the next step. The loop continues until the LLM’s output is a special action like FinalAnswer(...) indicating it is done, or until a predefined iteration limit is reached.

class ReActAgent:

def __init__(self, llm: PolicyLLM, tools: ToolRegistry, max_steps: int = 16):

self.llm = llm

self.tools = tools

self.max_steps = max_steps

def run(self, user_request: str) -> str:

transcript = “” # the full Thought/Action/Observation history

for step in range(self.max_steps):

prompt = build_react_prompt(user_request, transcript, self.tools.spec())

output = self.llm.generate(prompt)

transcript += “\n” + output

# Check for final answer

if “Final Answer:” in output:

# naive extraction; you can make this more robust

final = output.split(”Final Answer:”, 1)[1].strip()

return final

# Otherwise try to parse an Action:

action = extract_tool_call(output)

if action is None:

# Model didn’t produce a tool call or final answer; you might:

# - try again,

# - nudge via a fallback prompt,

# - or abort.

break

obs = self.tools.call(action.tool_name, action.tool_args or {})

transcript += f”\nObservation: {obs}”

return “I couldn’t complete this task in the allotted steps.”Planning and Execution

Planning is how the agent looks ahead and decomposes complex tasks. Even though LLMs can do some reasoning implicitly (via chain-of-thought prompting), in an agent we often want an explicit planning module or strategy to manage long tasks reliably. The agent (or a planning sub-module) tries to generate a complete plan of action before executing any step.

In Plan and Execute, we explicitly separate thinking about the whole task (planning) from doing each step (execution). At a high level, the agent works by taking in a user goal e.g. “Analyze our sales performance over the last 5 years and produce a slide-ready summary.” and operates in following steps:

Planner LLM generates a high-level plan

A planning prompt asks a (typically stronger) LLM to decompose the goal into a small number of concrete steps. For example,

Gather the relevant data.

Clean and aggregate by region and year.

Run basic trend analysis and detect anomalies.

Generate visualizations.

Summarize key insights in natural language.

The output is a structured plan e.g., a numbered list of steps.

(Optional) Plan review or editing

The plan can be shown to a human for approval, or passed through a “critic” LLM that checks for missing pieces, or lightly post-processed (e.g. enforce a max number of steps, normalize phrasing).

Executor loop runs each step as a subtask

For each step in the plan:

The Executor (which can be a cheaper LLM or an agent like ReAct) is invoked with a subtask description: “Subtask 2: Clean and aggregate sales data by region and year using the loaded dataset.”

The executor then decides which tools to use (e.g. compute in a Python REPL, search in a KB), runs its own inner loop of actions/observations, and returns a result for that subtask (e.g. a table, chart, or summary).

Share state across steps when needed

Some subtasks depend on outputs from previous steps (e.g. cleaned data used for analysis and plotting). The system maintains a shared state (e.g. data stored in the environment, or structured artifacts like “dataset_handle”, “plots”, “intermediate summaries”) that is passed to the executor for subsequent steps.

Error handling and re-planning

If a subtask fails (e.g. data source missing, code failing repeatedly), the executor returns a failure status or a structured error. The controller can adjust inputs and re-run that step, skip the step with a justification, or invoke the Planner again to revise the plan given what was learned (“Data source X was unavailable, propose an alternate plan”).

Plan-level aggregation and final answer

Once all steps are executed (or as many as feasible), a final LLM pass takes the original goal, the plan, and the results of each step, and synthesizes a final output: a report, a slide outline, a code patch, etc.

This pattern shines when tasks are long-horizon and decomposable, and where it’s beneficial to pay a one-time planning cost with a strong model, then execute cheaply and systematically.

class Planner:

def __init__(self, llm: PolicyLLM):

self.llm = llm

def make_plan(self, user_request: str) -> List[str]:

prompt = f”“”

You are a planning assistant.

Decompose the user’s request into a numbered list of concrete steps.

Keep each step short and executable.

User request:

{user_request}

“”“

text = self.llm.generate(prompt)

# e.g. parse lines starting with “1.”, “2.”, ...

steps = [line.split(”.”, 1)[1].strip()

for line in text.splitlines()

if line.strip().startswith(tuple(str(i) + “.” for i in range(1, 10)))]

return steps

class PlanAndExecuteAgent:

def __init__(self, planner: Planner, executor: ReActAgent):

self.planner = planner

self.executor = executor

def run(self, user_request: str) -> str:

steps = self.planner.make_plan(user_request)

# Optional: show the plan to the user or log it

# print(”Plan:”, steps)

# Execute each step as a sub-task with its own ReAct loop

sub_results = []

for step in steps:

sub_q = f”Subtask: {step}”

result = self.executor.run(sub_q)

sub_results.append((step, result))

# Combine into a final answer

final_answer = “Here is what I did:\n\n”

for step, result in sub_results:

final_answer += f”- {step}\n -> {result}\n”

return final_answerMulti-Agent Systems

Instead of a single monolithic agent, you can have multiple LLM agents that collaborate or compete to achieve a goal. Each agent might have a different role or specialization. Multi-agent systems can unleash emergent dynamics – for example, agents can critique each other’s ideas, or divide roles such as “planner” and “executor” (as we discussed, those could even be separate models).

A typical collaborative pattern looks like this:

Define roles and capabilities

Each agent is given a role prompt and possibly different tools. For example:

PlannerAgent: breaks tasks into subtasks, decides dependencies.

ResearchAgent: good at web/KB search and summarization.

CoderAgent: edits code, runs tests, fixes bugs.

ReviewerAgent: critiques proposals and suggests improvements.

Initialize a shared context / blackboard

The system maintains a shared memory or “blackboard” which stores:

the original user request,

the current state of work (plan, artifacts, logs),

messages between agents.

Each agent reads from and writes to this shared context when it acts.

Kick off the conversation with an initial message

Typically, the Coordinator (could be a specific agent or a thin controller) posts a starting message: “User request: build a REST API for X. Planner, please propose a plan”. This message is routed to the appropriate agent (PlannerAgent).

Turn-taking between agents

The system runs a loop where, on each turn:

It selects which agent should act next (simple round-robin, or based on explicit @mentions in messages, or via a coordinator policy).

That agent receives the shared context or a filtered view (e.g. last N messages), plus any artifacts relevant to its role (e.g. test logs for the CoderAgent).

The agent produces a message:

a plan update,

a question to another agent,

a tool call (e.g. run tests, search the web),

or a proposed final answer.

Tool use and environment interaction per agent

When an agent issues a tool call (e.g. CoderAgent calls run_tests(), ResearchAgent calls search_web()), the controller executes it in the environment and posts the observation back to the shared context as a reply message. That observation becomes available for all agents in subsequent turns (or filtered to those with access).

Coordination and conflict resolution

Agents can disagree or produce competing suggestions (e.g. ReviewerAgent criticizes CoderAgent’s patch). The coordinator (or a dedicated ArbiterAgent) can:

merge and summarize differing views,

ask for clarification (“Coder, address Reviewer’s concerns on X”),

or choose one proposal based on heuristics or a voting scheme.

Termination and final synthesis

The system needs clear stopping criteria, such as:

a specific agent (e.g. CoordinatorAgent) emits DONE with a final answer,

a maximum number of turns is reached,

or a target condition is satisfied (all tests pass, all subtasks marked complete).

A final “synthesis” agent or the Coordinator takes:

the user request,

the conversation trace,

and key artifacts (code, reports, tickets),

and generates the final output for the user.

(Optional) Logging and per-role evaluation

Because roles are separated, you can log and evaluate them independently:

how good are PlannerAgent’s decompositions?

how often does CoderAgent introduce regressions?

how helpful are ReviewerAgent’s comments?

This supports per-agent fine-tuning or replacement (swap in a stronger coder without touching the planner, etc.).

This pattern is powerful when tasks naturally decompose into roles or perspectives (planner vs executor, coder vs reviewer, researcher vs writer), and when you want explicit structure and specialization rather than one giant generalist agent doing everything in a single prompt.

@dataclass

class AgentRole:

name: str

system_prompt: str

tools: ToolRegistry

class MultiAgentOrchestrator:

def __init__(self, agents: Dict[str, Agent], coordinator_name: str):

self.agents = agents

self.coordinator = coordinator_name

self.shared_context: List[str] = []

def run(self, user_request: str, max_rounds: int = 10) -> str:

self.shared_context.append(f”User: {user_request}”)

for round_num in range(max_rounds):

# Simple round-robin; real systems use routing logic

for name, agent in self.agents.items():

prompt = self._build_agent_view(name)

response = agent.llm.generate(prompt)

self.shared_context.append(f”{name}: {response}”)

if “DONE:” in response and name == self.coordinator:

return response.split(”DONE:”, 1)[1].strip()

return “Max rounds reached without resolution.”

def _build_agent_view(self, agent_name: str) -> str:

# Each agent sees the shared context (could be filtered by role)

return “\n”.join(self.shared_context[-20:]) # Last 20 messagesTraining Agents

So far, we’ve treated the policy LLM as something we prompt into being a decent agent. But if we want an agent that is reliably good or want specific behaviour (especially with smaller models), we need to train it to learn this agentic behaviour.

The key difference between training a normal LLM and training an agent is the unit of learning. For a standard assistant, we train on single-turn (prompt → response) pairs. For an agent, that’s usually not enough, because the interesting behavior lives between the first prompt and the final answer. The policy needs to learn tool selection, argument formatting, recovery from errors, and deciding when to stop. In other words, agents generate proper trajectories.

A trajectory is one full episode of interaction:

the state the agent saw (user request + history + tool outputs),

the actions it chose (tool calls and the final answer),

and the observations the environment returned (tool results, logs, errors).

Once you can record this loop as data, training becomes conceptually straightforward: run the agent → score the episode → update the policy to get higher-scoring episodes more often.

Here’s the minimal object you want to log (and later train on):

@dataclass

class Trajectory:

observations: List[str]

actions: List[AgentAction]

final_answer: str

metadata: Dict[str, Any] # e.g. unit test results, environment logsWhere rewards come from

For agentic tasks, the cleanest rewards come from external checks. A coding agent has unit tests. A data analysis agent can be graded on whether a computed value matches ground truth. A workflow agent can be graded on whether it successfully completed a sequence of API operations without violations.

That means we typically define an episodic reward which is a number assigned to the whole run. In the simplest case:

reward = 1 if success, else 0

from typing import List

def extract_final_integer(text: str) -> int:

# toy extractor: pick the last integer in the string

import re

matches = re.findall(r”-?\d+”, text)

return int(matches[-1]) if matches else None

def correctness_reward_func(

responses: List[str],

golds: List[str],

) -> List[float]:

rewards = []

for resp, gt in zip(responses, golds):

pred = extract_final_integer(resp)

try:

g_int = int(gt) if gt is not None else None

except ValueError:

g_int = None

reward = 2.0 if (pred is not None and g_int is not None and pred == g_int) else 0.0

rewards.append(reward)

return rewardsFor agentic tasks (e.g. coding, data analysis), we often have:

a trajectory:

(s_0, a_0, o_0, ..., s_T, a_T)a final outcome: pass/fail, or numeric score.

We can implement a simple episodic reward:

def compute_episode_reward(traj: Trajectory) -> float:

“”“

Example: for a coding agent, reward = 1.0 if unit tests pass, else 0.0

“”“

tests_passed = traj.metadata.get(”tests_passed”, False)

return 1.0 if tests_passed else 0.0The agent loop gives a consistent place to attach the reward: at the end of the episode, after the environment has verified success.

Training Process

Phase 1 - Teach the protocol: Before we optimize anything, the model needs to reliably speak the “agent language”: emitting valid tool-call JSON, choosing existing tools, producing arguments that validate, and responding with a final answer in the expected format. This is where supervised fine-tuning shines. Collect good trajectories (human-written, or produced by a stronger teacher agent) and train the policy to imitate the next action given the current state.

Phase 2 - Optimize outcomes : Once the policy is competent at participating in the loop, RL becomes the knob we use to optimize what you actually care about: pass the tests, get the right number, finish in fewer steps, avoid tool misuse, recover when something breaks. Here the agent loop is literally your RL environment: the policy proposes actions, the environment responds with observations, and a reward arrives based on outcome. This is where methods like PPO / GRPO / RLOO enter.

Credit assignment, without getting lost in equations

One reason agents are hard is credit assignment. Success usually depends on a sequence of tool calls, not one token. If the only signal is “tests passed at the end”, learning can be noisy. The usual practical fix is to keep the reward definition anchored in the final outcome, but add gentle structure around it:

limit steps (so the policy learns efficiency),

penalize repeated failed tool calls,

reward progress signals the environment can verify (e.g., “failing tests reduced from 12 → 3”).

What makes training actually work: replayability

The unglamorous but decisive detail is logging. If you can’t replay and inspect failures, you can’t iterate on rewards, prompts, or tool interfaces. A good agent training setup therefore treats each episode like an experiment record:

exact prompts shown at each step,

exact tool calls emitted (the raw JSON),

exact tool outputs/errors returned,

final evaluation artifact (test report, numeric metric, etc.).

Key Challenges

LLM agents are powerful precisely because they’re autonomous and multi-step. But they are also hard to build. Many failure modes are familiar from vanilla LLMs (hallucinations, sensitivity to prompts), but the moment you add tools, memory, and an execution loop, those issues become operational. The agent can now take the wrong action, get stuck, leak information, or silently corrupt state. Below are the main challenges that show up in practice.

Reliability and robustness

A reliable agent consistently takes the right steps and produces correct outcomes. A robust agent keeps working when inputs, tool outputs, or the environment change in unexpected ways. Today’s agents are often brittle e.g. small changes in phrasing, context length, or tool output formatting can cause the policy to derail. Common symptoms include hallucinating tools or arguments, misreading observations (especially error traces), looping without progress, and “forgetting” key constraints when the context window fills and summaries drop important details. Integration adds another sharp edge - even a minor mismatch in an API response schema can cascade into downstream failures because the agent’s next decisions depend on parsing those outputs correctly.

In production, reliability is less about clever prompting and more about engineering the loop so it can’t catastrophically fail. That usually means validating tool calls (allowlist tools, validate JSON), adding explicit error-recovery behaviors (retry with backoff, alternative strategies, ask for help), enforcing step budgets and stopping criteria to prevent thrashing, and continuously regression-testing the agent on a fixed evaluation suite.

Effective tool use and search

Giving an agent tools is easy, getting it to use them well is the real work. The agent has to

recognize when it should stop guessing and call a tool

choose the right tool among several

form valid, minimal arguments (especially for strict schemas)

interpret tool outputs correctly

sanity-check results rather than blindly trusting whatever text came back from a search or document.

One can improve this with clearer tool descriptions, few-shot exemplars of correct tool use (including how to react to errors), schema enforcement with automatic retries, and simple external heuristics (e.g., route obvious calculations to a calculator tool). Longer-term, tool-use fine-tuning on good trajectories helps, because it teaches the model not just how to call tools, but when and why.

Long-horizon credit assignment

Agents fail in ways that are hard to diagnose because the outcome depends on a sequence of decisions. If a run fails after 20 steps, which step caused it? A wrong assumption early can poison everything that follows, and many environments don’t provide step-level rewards or clear intermediate checkpoints. This is the classic credit assignment problem: both for training (how to update the policy) and for debugging (how to identify the root cause).

Practically, teams address this by breaking tasks into verifiable subtasks, adding checkpoints (unit tests, intermediate validations), replan periodically to avoid compounding errors, and using retrospective analysis, sometimes even asking a separate model to inspect a trajectory and point to the earliest plausible mistake. RL research adds techniques for step-wise rewards or critics, but even without them, good instrumentation and intermediate verification are often the difference between an agent that improves and one that remains mysterious.

Cost and latency

Agent loops multiply cost and delay: instead of one model call, you may have ten model calls plus slow tools (web search, remote APIs, test runs). Because the loop is sequential — observe, decide, act — latency adds up. This matters in real deployments where users feel the difference between a 2-second answer and a 20-second agent run.

Common mitigations involve use strong models selectively (plan/final synthesis) and cheaper models for routine steps, cap steps and tool retries, cache and reuse tool results, and parallelize independent tool calls where possible. And sometimes the best optimization is the simplest - don’t invoke an agent at all unless the task truly needs multi-step interaction.

Evaluation, safety, and governance

Evaluating agents is harder than grading single answers because you care about process as well as outcome: did the agent follow allowed procedures, use tools responsibly, finish efficiently, and avoid unsafe actions? Many tasks also lack clean ground truth, so evaluation becomes a mix of automated checks (tests, success conditions, policy violations) and human judgment.

Safety and security become first-class concerns once agents can act. Tool outputs (especially web pages) are untrusted and can contain prompt-injection attempts; sensitive tools (email, file writes, purchases) require permissioning and often human approval; sandboxes and least-privilege access are non-negotiable. A practical governance posture treats the agent like potentially buggy code: log actions, validate inputs/outputs, isolate execution, monitor for abnormal behavior, and keep a human in the loop for irreversible operations.

Conclusion

In this post, we explored the world of LLM-based agents, and wrote a minimal agent stub. In my next, I’ll share agents that I am building. Stay tuned!

LLM-based agents are often described as “LLMs with a body and a job”.

The body is the machinery around the model: tools, environment interfaces, memory, and guardrails.

The job is the objective: a user goal, success criteria, and (optionally) a reward signal.

The core abstraction fits in a few dozen lines. The workflow is a loop that repeatedly observes, decides, acts, and incorporates the result. What makes agents powerful is not architectural complexity but composability. A tool registry lets you snap in new capabilities (a database, a browser, a code interpreter) without rewriting the core logic. A memory module lets you scale from single-turn Q&A to multi-session assistants. A reward function lets you turn the same loop into a training environment. Each component is simple; the product is greater than the sum.

That said, the hard problems remain hard:

Reliability: Getting an agent to use tools correctly 99% of the time is straightforward; getting to 99.9% is an open research problem. Parse failures, hallucinated function names, and off-by-one errors in multi-step reasoning compound quickly.

Credit assignment: When a ten-step trajectory fails, which step was the mistake? RL can help, but sparse rewards and long horizons make learning slow. Better intermediate signals (verifiers, critics, process rewards) are an active area of work.

Control vs. autonomy: Fully autonomous agents are powerful but dangerous. Workflow-orchestrated agents are safer but brittle. The right balance depends on the stakes: a data analysis assistant can afford more autonomy than an agent executing financial transactions.

Evaluation: It’s easy to demo an agent succeeding on a cherry-picked task. It’s hard to build a benchmark that captures the distribution of real-world failures. Without good evaluation, we’re flying blind.

If there’s one takeaway from this post, it’s that agents are not mystical. They’re software systems with well-defined interfaces: an LLM as the policy, tools as the action space, observations as the state, and rewards (explicit or implicit) as the objective. You can debug them, profile them, and improve them with the same discipline you’d apply to any other system.

As these systems mature, expect tighter integration between symbolic planning, neural reasoning, and verified execution. The agents that make it to production won’t be the most autonomous; they’ll be the ones that fail gracefully, explain their reasoning, and know when to ask for help. Building those agents is the work ahead.

If you find this post useful, I would appreciate if you can cite it as:

@misc{verma2025llm-based-agents,

title={LLM-based Agents

year={2025},

url={\url{https://januverma.substack.com/p/llm-based-agents}},

note={Incomplete Distillation}

}

++ Good Post, Also, start here how to build tech, Crash Courses, 100+ Most Asked ML System Design Case Studies and LLM System Design

How to Build Tech

https://open.substack.com/pub/howtobuildtech/p/how-to-build-tech-10-how-to-actually?r=14q3sp&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=false

https://open.substack.com/pub/howtobuildtech/p/how-to-build-tech-06-how-to-actually?r=14q3sp&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=false

https://open.substack.com/pub/howtobuildtech/p/how-to-build-tech-05-how-to-actually?r=14q3sp&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=false

https://open.substack.com/pub/howtobuildtech/p/how-to-build-tech-04-how-to-actually?r=14q3sp&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=false

https://open.substack.com/pub/howtobuildtech/p/how-to-build-tech-03-how-to-actually?r=14q3sp&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=false

https://open.substack.com/pub/howtobuildtech/p/how-to-build-tech-01-the-heart-of?r=14q3sp&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=false

https://open.substack.com/pub/howtobuildtech/p/how-to-build-tech-02-how-to-actually?r=14q3sp&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=false

Crash Courses

https://open.substack.com/pub/crashcourses/p/crash-course-07-hands-on-crash-course?utm_campaign=post-expanded-share&utm_medium=web

https://open.substack.com/pub/crashcourses/p/crash-course-06-part-2-hands-on-crash?utm_campaign=post-expanded-share&utm_medium=web

https://open.substack.com/pub/crashcourses/p/crash-course-04-hands-on-crash-course?r=14q3sp&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=false

https://open.substack.com/pub/crashcourses/p/crash-course-03-hands-on-crash-course?r=14q3sp&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=false

https://open.substack.com/pub/crashcourses/p/crash-course-02-a-complete-crash?r=14q3sp&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=false

https://open.substack.com/pub/crashcourses/p/crash-course-01-a-complete-crash?r=14q3sp&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=false

LLM System Design

https://open.substack.com/pub/naina0405/p/very-important-llm-system-design-577?utm_campaign=post-expanded-share&utm_medium=web

https://open.substack.com/pub/naina0405/p/very-important-llm-system-design-4ea?utm_campaign=post-expanded-share&utm_medium=web

https://open.substack.com/pub/naina0405/p/very-important-llm-system-design-499?r=14q3sp&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=false

https://open.substack.com/pub/naina0405/p/very-important-llm-system-design-63c?r=14q3sp&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=false

https://open.substack.com/pub/naina0405/p/very-important-llm-system-design-bdd?r=14q3sp&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=false

https://open.substack.com/pub/naina0405/p/very-important-llm-system-design-661?r=14q3sp&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=false

https://open.substack.com/pub/naina0405/p/very-important-llm-system-design-83b?r=14q3sp&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=false

https://open.substack.com/pub/naina0405/p/very-important-llm-system-design-799?r=14q3sp&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=false

https://open.substack.com/pub/naina0405/p/very-important-llm-system-design-612?r=14q3sp&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=false

https://open.substack.com/pub/naina0405/p/very-important-llm-system-design-7e6?r=14q3sp&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=false

https://open.substack.com/pub/naina0405/p/very-important-llm-system-design-67d?r=14q3sp&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=false

https://open.substack.com/pub/naina0405/p/most-important-llm-system-design-b31?r=14q3sp&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=false

https://naina0405.substack.com/p/launching-llm-system-design-large?r=14q3sp

https://naina0405.substack.com/p/launching-llm-system-design-2-large?r=14q3sp

[https://open.substack.com/pub/naina0405/p/llm-system-design-3-large-language?r=14q3sp&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=false

https://open.substack.com/pub/naina0405/p/important-llm-system-design-4-heart?r=14q3sp&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=false

https://open.substack.com/pub/naina0405/p/very-important-llm-system-design-63c?r=14q3sp&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=false

Really solid breakdown of the observe→decide→act loop. The memroy architecture piece is underappreciated, especially how short-term gets saturated fast and you need semantic retrieval for anything non-trivial. I've run into this with coding agents where the execution history fills the context so quickly that the model forgets earlier constraints, which is exactly the long-term vector store problem you descirbe.