Graph Foundation Models

building GPT for graphs

Foundation Models

A foundation model is a large model trained on broad data that can be adapted to many different tasks without starting from scratch. The term comes from a 2021 Stanford paper that named the paradigm: you build a “foundation” once, then build many things on top of it.

Traditionally machine learning is repetitive and problem-specific. Want to detect spam? Collect spam labels, train a model. Want to classify sentiment? Collect sentiment labels, train another model. Every task started from zero.

Foundation models break this cycle. GPT models were trained on single task of predicting the next word using text from the internet. Nobody labelled anything. Yet that single model could then be used to translate languages, write code, answer questions, and summarize documents. The “foundation” supported many buildings.

Three ingredients make this work:

Self-supervision: Training signal comes from the data itself. Predict the next word. Predict whether an image patch is masked. No expensive human labelling.

Scale: Billions of parameters trained on terabytes of data. Empirically, performance improves predictably as you scale up.

Transfer: Skills learned during pre-training generalize to tasks never explicitly trained for. This was the surprising discovery that made the paradigm valuable.

The practical impact is enormous. Instead of months of data collection and training for each task, you prompt a pre-trained model or fine-tune it with a handful of examples.

Graphs Foundation Models

Graphs are everywhere in consequential applications:

Banks model transactions as graphs to catch fraud

Social platforms model users and content as graphs to detect manipulation

Pharmaceutical companies model molecules as graphs to predict drug properties

Security teams model network traffic as graphs to find intrusions

These applications share a painful reality: labelled data is scarce and expensive.

Consider the problem of fraud detection. A bank might process billions of transactions but have confirmed fraud labels for only thousands. New fraud patterns emerge constantly, and by the time we collect enough examples to train a detector, the fraudsters have moved on.

Or consider molecular property prediction where synthesizing and testing a molecule costs thousands of dollars. You cannot generate abundant labels by throwing money at the problem.

The foundation model promise is compelling here. Pre-train on the abundant unlabelled graph structure, then adapt to specific tasks with minimal labels. Detect new fraud patterns with ten examples instead of ten thousand. Predict molecular toxicity without synthesizing every candidate

What a Graph Foundation Model Would Need

To build a GFM, you need solutions to several problems:

A way to handle any graph structure. Graphs vary wildly. A molecule has tens of atoms with regular bonding patterns. A social network has billions of users with power-law degree distributions. A GFM must process both without architecture changes.

A way to handle heterogeneous types. Real graphs have multiple node types (users, posts, pages) and edge types (follows, likes, comments). The model must represent and reason about these distinctions.

A way to handle heterogeneous features. Different node types have different features. A user has age and location. A post has text and images. A transaction has amount and timestamp. Feature spaces don’t align across types.

A self-supervised pre-training task. You need a task that requires no labels and teaches the model useful structure. Language models predict next tokens. What should graph models predict?

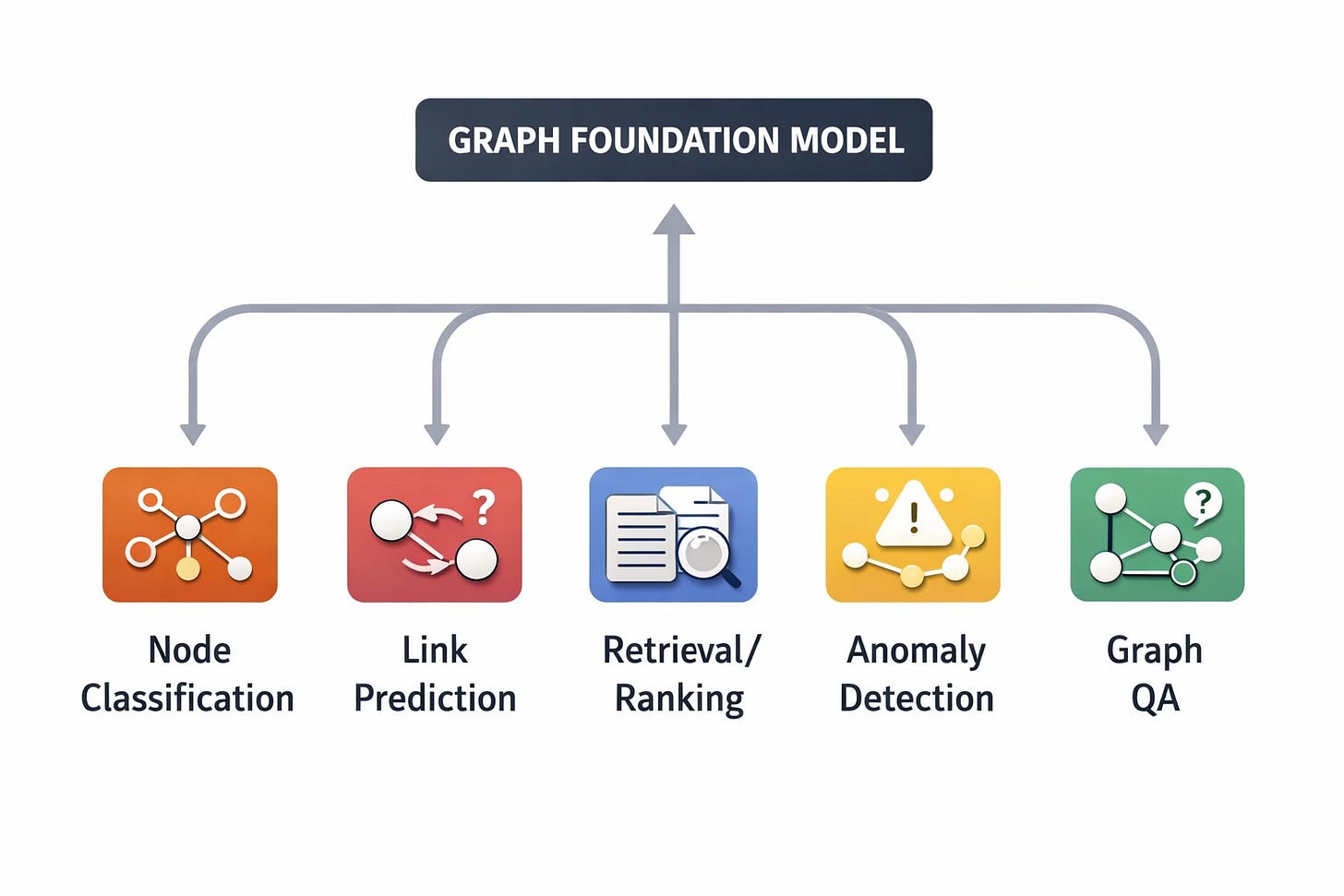

A way to adapt to different downstream tasks. Graph problems span node classification (is this account fake?), link prediction (will this user click this ad?), and graph classification (is this molecule toxic?). The foundation must support all.

A way to scale. Industrial graphs have billions of nodes and edges. The model and training pipeline must handle this without collapsing.

Why Graph Foundation Models Are Difficult

Each requirement presents serious challenges.

The Heterogeneity Problem

Text has one token type. Images have pixels on a fixed grid. Graphs have arbitrary node types, edge types, and feature dimensions.

Consider pre-training on social network data and then applying to molecular data. Social networks have users with demographic features connected by “follows” edges. Molecules have atoms with chemical features connected by bond edges. The node types differ. The edge types differ. The feature dimensions differ. How do you even feed molecular data into a model pre-trained on social data?

Some approaches restrict inputs to a predefined vocabulary, like language models do. Others group features into broad categories (numerical, categorical, text) and apply shared transformations within each group. Both approaches sacrifice expressivity for compatibility.

The Scale Problem

A standard transformer computes attention between all pairs of tokens. For a sequence of length n, this costs O(n²). Language models handle this because sequences are thousands of tokens.

Graphs are different. A node might have millions of neighbors. Computing full attention over a neighbourhood is impossible. But sampling neighbors throws away information. How do you balance expressivity and efficiency?

The Distribution Problem

Real graphs have severe imbalances. Some node types are common, others rare. Some edge types appear billions of times, others thousands. Standard training will learn common patterns well and rare patterns poorly—but rare patterns often matter most (rare fraud types, unusual molecular structures).

The Transfer Problem

Even if you solve the above, will pre-training actually help? Graph distributions differ more than text distributions. English sentences and French sentences share structure. Social networks and molecular graphs share what exactly? It is not obvious that pre-training on one graph teaches anything useful for another.

GraphBFF

A new paper from Meta presents GraphBFF (Graph Billion-Foundation-Fusion), the first complete framework for building billion-parameter foundation models for graphs.

Key Insight: Foundation Models are Graph Models

Chaitanya Joshi has written about framing transformers as graph neural networks in great details.

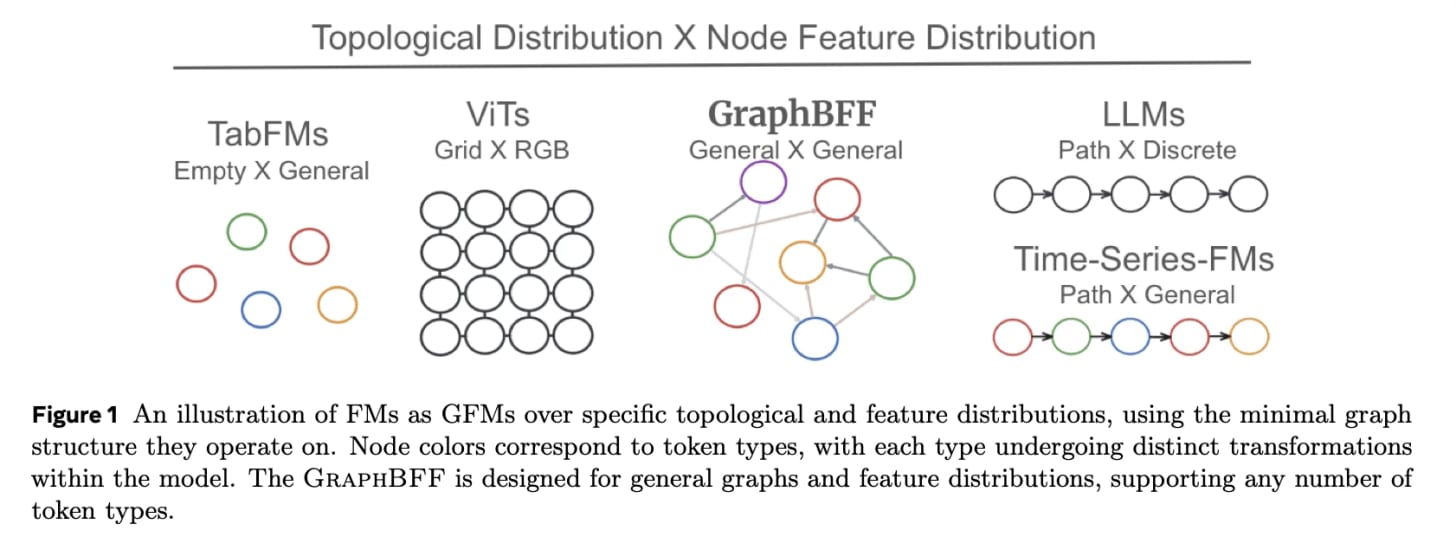

The paper leverages this clever observation: existing foundation models can be viewed as specialized graph models:

LLMs operate on path graphs (sequential tokens)

Vision Transformers operate on 2D grid graphs (pixels)

GraphBFF handles arbitrary graph structure

GraphBFF provides concrete solutions to each of the challenges we discussed above. The paper presents both an architecture (GraphBFF Transformer) and a complete training recipe.

Handling Heterogeneity: Two Attention Mechanisms

The GraphBFF Transformer combines two attention components:

Type-Conditioned Attention (TCA) maintains separate attention computations for each edge type. When a node attends to its neighbors, it does so within edge-type groups. A user node attends separately to followed accounts and liked posts, with different learned parameters for each.

Crucially, softmax normalization happens within each edge type, not across all neighbours. This prevents common edge types from drowning out rare ones in the attention weights.

Type-Agnostic Attention (TAA) applies shared attention across all edge types. This allows information to flow across type boundaries. A user’s representation can be influenced by posts and other users jointly. To manage scale, TAA samples a fixed number of neighbors rather than attending to all of them.

The paper proves mathematically that you need both components. There exist functions that TCA alone cannot compute (because it cannot see cross-type cardinality) and functions that TAA alone cannot compute (because it cannot distinguish edge types). Together, they cover both cases.

Handling Scale: Smart Batching

Training on billion-edge graphs requires partitioning data into batches that fit in memory. Naive partitioning creates problems:

Random clusters may have very different type distributions than the full graph

Early training batches can bias the model toward whatever types they happen to contain

Common edge types can dominate gradient updates, starving rare types

GraphBFF introduces two batching strategies:

KL-Batching operates at storage level. It clusters the graph, measures each cluster’s type distribution against the global distribution using KL divergence, and assembles batches from clusters that best match the global distribution. This ensures each batch is representative.

Round-Robin Batching operates at GPU level. Instead of randomly sampling edges for each mini-batch, it cycles through edge types in fixed order. Each type gets equal attention regardless of frequency.

Pretraining Task: Masked Link Prediction

For self-supervision, GraphBFF uses masked link prediction: hide some edges, train the model to predict whether they exist. This is analogous to masked language modeling in BERT.

The paper notes that many sophisticated self-supervised objectives have been proposed for graphs. They conjecture, and their results support, that a simple objective at sufficient scale is enough. Complexity in the pretraining task may be unnecessary if you have enough data and parameters.

Demonstrating Transfer: Extensive Evaluation

The paper trains a 1.4 billion parameter model on one billion edges and evaluates on ten diverse downstream tasks from different domains. Crucially, the evaluation graphs are completely separate from pre-training data with no shared nodes or edges.

Results show strong transfer:

Probing (freezing the model and training a small classifier on its outputs) beats fully-trained task-specific models on all ten tasks

Few-shot performance with 10 examples often matches task-specific models trained on full datasets

On one task, the gap is 52 PRAUC points which is more than an incremental improvement but a qualitative change

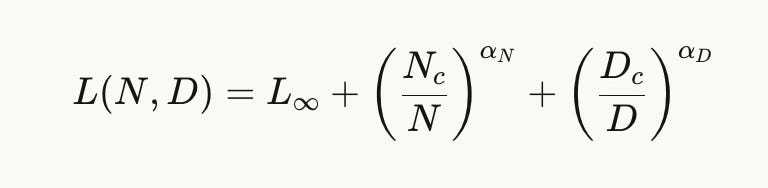

Establishing Scaling Laws

A major contribution is demonstrating that GFMs follow predictable scaling laws. Validation loss decreases as a power law in both model size and data size:

This matters because it means GFM development is predictable. You can estimate how much performance you will gain from more compute. You can identify whether you are bottlenecked by model capacity or data. The same planning tools that guide LLM development now apply to graphs.

The fitted exponents (αN ≈ 0.703, αD ≈ 0.188) show that both model size and data size matter, and gains require scaling both together.

Epilogue: GraphBFF as a Foundation Model

I have difficulty grasping the idea of these models as foundation model in the same way as LLMs or VLMs. The internet provides text for the LLM to train on, which contains Wikipedia, books, Reddit, code, news, scientific papers. This corpus contains data across many languages, many domains, many writing styles, and many topics. When you prompt GPT with a new piece of text, it has probably seen something similar during training. The “foundation” is truly general because the training data was truly diverse. Same model is used for code generation and text completion in multiple languages. Whereas the graphs are all different, there is no global data of all the graphs. Formally, text has a universal alphabet (tokens) and the internet is one giant, loosely coherent distribution; graphs often look like bespoke objects with arbitrary node IDs and incompatible schemas.

GraphBFF trained on one graph which is Meta’s internal graph with ~50 billion nodes and edges, covering social connections, financial transactions, business relationships, and infrastructure. The downstream tasks were evaluated on different parts of graphs within that same universe i.e. different nodes and edges, but the same types of entities and relationships. This is not the same as training on “all graphs.” A molecular graph has atoms and bonds. A citation network has papers and citations. These share nothing with Meta’s social-financial graph except the abstract concept of “nodes and edges.”

The paper’s claim is more modest than “one model for all graphs.” What they are showing is:

Within a large heterogeneous graph ecosystem, pretraining helps.

The model learns patterns like:

How user entities relate to content entities

How financial signals propagate through transaction networks

How different relationship types carry different information

These patterns transfer to new fraud detection tasks, new content classification tasks, new attribution problems as long as they involve the same kinds of entities and relationships.

A better analogy would be to think of it less like “GPT for graphs” and more like “a domain-specific language model.”

If you trained a language model only on legal documents, it would:

Excel at new legal tasks (contract analysis, case summarization)

Fail at poetry or casual conversation

Still be valuable because legal expertise transfers across legal problems

GraphBFF is similar. It is a foundation model for Meta’s graph universe. Within that universe, the foundation is solid. Outside it, the model would need retraining.

The paper acknowledges this. In the Discussion section, the authors explicitly flag this as an open problem:

“While it is always possible to merge all available graphs into a single pre-training corpus, it is unclear whether this is optimal, and whether it would yield the best generalization across downstream tasks.”

An interesting setup is if you combined social graphs, molecular graphs, and citation networks into one pre-training corpus, would that help or hurt? Would patterns from molecules transfer to social networks? Nobody knows yet, at least I am not aware of any work in this direction.

Even with this limitation, the contribution matters for practical reasons:

Large organizations have massive unified graphs. Meta, Google, banks, and telecom companies maintain graphs with billions of nodes spanning many entity types. For them, “one foundation model for our graph” is enormously valuable even if it doesn’t generalize to molecular chemistry.

The recipe might transfer even if the weights don’t. The architecture, batching strategies, and training methodology could work for any large graph. A pharmaceutical company could follow the same recipe on their molecular data.

It establishes that graph pre-training works at all. This work shows that self-supervised pre-training on graphs produces transferable representations, at least within a graph universe.

The honest summary is that GraphBFF is not “one model for all graphs” the way GPT is “one model for all text.” It is closer to:

One model per large graph ecosystem

Or one model per domain (social, molecular, citation)

With an open question about whether cross-domain transfer is possible

The paper is a proof of concept that the foundation model paradigm applies to graphs. Making it truly universal, if that is even possible, remains future work.

If you find this post useful, I would appreciate if you cite it as:

@misc{verma2026graph-foundation-models,

title={Graph Foundation Models

year={2026},

url={\url{https://januverma.substack.com/p/graph-foundation-models}},

note={Incomplete Distillation}

}